Muscles Of The Body - Front

Muscles Of The Face

Frontalis

The frontal belly of epicranius muscle (also known as the frontalis muscle), with assistance from the occipital belly, pulls the scalp back so that the eyebrows are lifted and the forehead can wrinkle. The epicranius muscle is a wide musculofibrous layer that wraps around one entire side of the vertex of the skull, from the occipital bone to the eyebrow. It's made up of two muscles: the occipitalis and the frontalis.

The frontalis muscle takes on a thin, quadrilateral form.

This muscle is wider than the occipitalis and its fibres are lighter in color and longer. There are no bony attachments. The medial fibres are connected with those of the Procerus; the corrugator and the orbicularis oculi mix with its immediate fibres. Its lateral fibres also mix with the latter muscle over the zygomatic process of the frontal bone.

At these attachments, the fibres move up and join the galea aponeurotica beneath the coronal suture. The medial margins of the frontales move together for a while above the root of the nose; however, between the occipitales there is a significant, though changing interval taken up by the galea aponeurotica.

Orbicularis Oculi

The orbicularis oculi muscle is one of the two major components that form the core of the eyelid, the other being the tarsal plate. The orbicularis oculi muscle is composed of skeletal muscle fibers, and receives nerves from the facial nerve. It is an important muscle in facial expression.

The orbicularis oculi muscle lies directly underneath the surface the skin, around the eyes. Its function is to close the eyelid, and to help in the passing and draining of tears through the punctum, canaliculi, and lacrimal sac, all parts of the tear drainage system.

The orbicularis oculi muscle is composed of three parts: the orbital portion, the palpebral portion, and the lacrimal portion. The orbital portion closes the eyelids firmly and is controlled by voluntary action. The palpebral portion closes the eyelids gently in involuntary or reflex blinking. The palpebral portion is divided into three parts; the pretarsal portion, the preseptal portion, and the ciliary portion. The lacrimal portion compresses the lacrimal sac, which receives tears from the lacrimal ducts and conveys them into the nasolacrimal duct.

Facial paralysis often affects the orbicularis oculi muscle. Inability to close the eye causes it to dry out, resulting in pain or even blindness in extreme cases.

Corrugator Supercilii

The corrugator supercilii is a muscle of the face. Situated immediately beneath either eyebrow toward the bridge of the nose, it is found at the very top of the eye socket between the frontalis muscle of the forehead and the orbicularis oculi muscle of the eyelid. When contracting, this muscle pulls the eyebrows down and in toward the nose, producing a frown or other expression of displeasure or discomfort. In addition, the corrugator supercilii is the muscle used to squint against bright light, as it pulls the brow forward to shield the eyes.

Located just below the eyebrows and with fibres running parallel to the medial portion of the eyebrow — the portion of the brow to the inside of the arch — the corrugator supercilii originates on the superciliary arch. The superciliary arch is a curved bony prominence on the frontal bone that can be felt behind either eyebrow. This muscle arises between the eyebrows from the innermost end of either arch. When it contracts, it produces several vertical folds between the brows, giving the muscle the name corrugator, as in corrugated cardboard.

From the superciliary arches, the corrugator supercilii directs lateralward, its fibres ascending slightly toward the arch of the eyebrow. The muscle tapers before inserting into the underside of the skin just above the orbital arch, the ridge at the top of the eye socket, at its centermost point. From its point of origin to its point of insertion, this muscle is perhaps an inch long.

Procerus

The procerus muscle is the pyramid-shaped muscle extending from the lower part of the nasal bone to the middle area in the forehead between the eyebrows, where it is attached to the frontalis muscle. Its location allows it to pull the skin between the eyebrows down.

Its surface is marked with transverse (horizontal) lines and it is usually one of the sites targeted during treatment or correction of wrinkles. Over-activity of the procerus muscle and corrugator supercilii results in the appearance of wrinkles. Researchers in the field of plastic surgery who are looking into possible remedies for transverse wrinkles and glabellar frown lines — the vertical wrinkles that people develop between their eyebrows — study the structure and function of the procerus muscle. They use specimens taken from the buccal branch of the superior orbital nerve.

Orbicularis Oris

Located in the face, the orbicularis oris muscle controls movements of the mouth and lips. Specifically, it encircles the mouth, originating in the maxilla (upper jaw and palate) and mandible (lower jaw) bones. The muscle inserts directly into the lips.

In common language, the orbicularis oris is often referred to as "the kissing muscle." It allows for facial expression, and more specifically, it is responsible for puckering the lips. While this action is a requirement for kissing, the puckering action is used in a number of other ways. For example, the lips must contract into a pucker to forcefully exhale, which is necessary for playing certain music instruments such as trumpets and other horns. The orbicularis oris muscle is also responsible for closing the mouth.

In the past, the muscle was thought to be a sphincter, which is a ring-like muscle used to open or close an area of the body. Recently, it has been found to not exactly meet that definition, even though it does perform sphincter-like opening and closing actions.

The muscle is supplied by the seventh cranial nerve, as well as the buccal branch of the facial nerve.

Upper Body Muscles

MUSCLES OF THE UPPER BODY

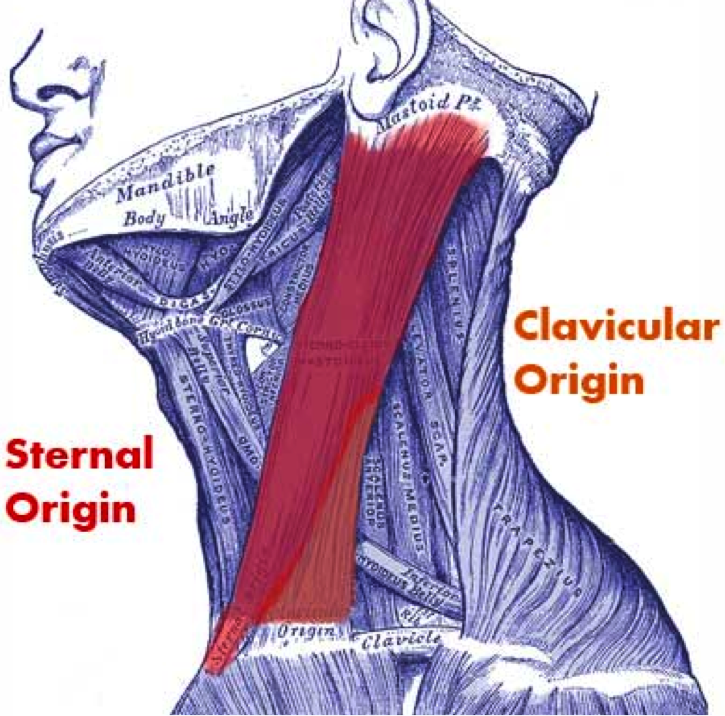

Sternocleidomastoid

The sternocleidomastoid muscle flexes the neck and helps with movement of the head. Also, the muscle works with the scalene muscles in the neck during forced inspiration while breathing (inhaling), and it raises the sternum, the bone at the front of the rib cage.

The muscle originates at the central portion of the collarbone. It inserts into the temporal bone's mastoid process near the ear and the base of the skull, and it stretches the entire length of the neck. This muscle helps the neck to turn to the side, flex to the side, and bend forward.

Two nerves serve the sternocleidomastoid muscle. For motor functions (movement), the muscle uses the accessory nerve. The cervical plexus nerve provides for sensory function, which includes proprioception — the sense we have of our body’s position and movement within the space around us. This function applies only to the inner workings of the body. For this muscle, proprioception involves becoming aware of pain and transmitting signals to the brain.

Two arteries serve the sternocleidomastoid. Oxygenated blood arrives at the muscle via the occipital artery in the head and superior thyroid artery in the neck.

Deltoid

The deltoid muscle is located on the outer aspect of the shoulder and is recognised by its triangular shape. The deltoid muscle was named after the Greek letter Delta due to the similar shape they both share. The deltoid muscle is constructed with three main sets of fibres: anterior, middle, and posterior. These fibres are connected by a very thick tendon and are anchored into a V-shaped channel. This channel housed in the shaft of the humerus bone in the arm. The deltoid muscle is responsible for the brunt of all arm rotation and allows a person to keep carried objects at a safer distance from the body. It is also tasked with stopping dislocation and injury to the humerus when carrying heavy loads. One of the most common injuries to the deltoid muscle is a deltoid strain. Deltoid strain is characterised by sudden and sharp pain where injured, intense soreness and pain when lifting the arm out from the side of the body, and tenderness and swelling caused by (and located at) the deltoid muscle.

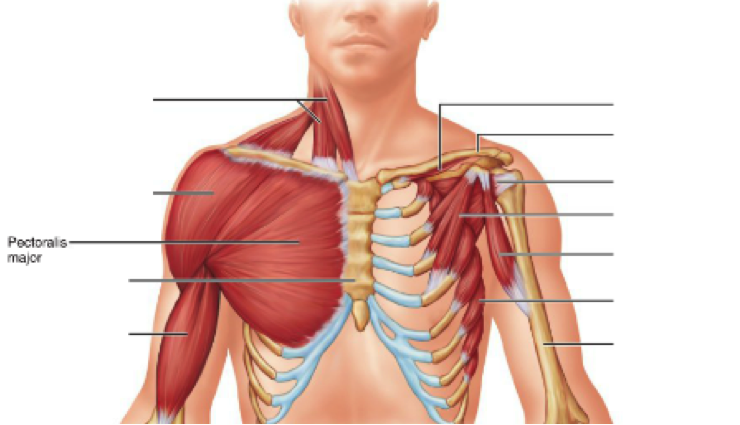

Pectoralis Major

The pectoralis major muscle is a large muscle in the upper chest, fanning across the chest from the shoulder to the breastbone. The two pectoralis major muscles, commonly referred to as the "pecs," are the muscles that create the bulk of the chest. A developed pectoralis major is most evident in males, as the breasts of a female typically hide the pectoral muscles. A second pectoral muscle, the pectoralis minor, lies beneath the pectoralis major. The pectorals are predominantly used to control the movement of the arm, with the contractions of the pectoralis major pulling on the humerus to create lateral, vertical, or rotational motion. The pectorals also play a part in deep inhalation, pulling the ribcage to create room for the lungs to expand. Six separate sets of muscle fibre have been identified within the pectoralis major muscle, allowing portions of the muscle to be moved independently by the nervous system. Injuries to the pectoralis major can occur during weightlifting, as well as other bodybuilding exercises that place excessive strain on the shoulders and chest.

Biceps

The biceps brachii, sometimes known simply as the biceps, is a skeletal muscle that is involved in the movement of the elbow and shoulder. It is a double-headed muscle, meaning that it has two points of origin or "heads" in the shoulder area. The short head of each biceps brachii originates at the top of the scapula (at the coracoid process). The long head originates just above the shoulder joint (at the supraglenoid tubercle). Both heads are joined at the elbow. The biceps brachii is a bi-articular muscle, which means that it helps control the motion of two different joints, the shoulder and the elbow. The function of the biceps at the elbow is essential to the function of the forearm in lifting. The function of the biceps brachii at the shoulder is less pronounced, playing minor roles in moving the arms forward, upward, and sideways. Although it is generally considered to be doubled headed, the biceps brachii is one of the most variable muscles in the human body. It is common for human biceps to have a third head originating at the humerus. As many as seven heads have been reported.

Serratus

The serratus anterior a muscle that originates on the top surface of the eight or nine upper ribs. The serratus anterior muscle inserts exactly at the front border of the scapula, or shoulder blade. The muscle has three sections: the superior, intermediate or medial, and the inferior. The function of the serratus anterior muscle is to allow the forward rotation of the arm and to pull the scapula forward and around the rib cage. The scapula is able to move laterally due to the serratus anterior muscle, which is vital for the elevation of the arm. The serratus anterior muscle also allows the upward rotation of the arm, which allows a person to lift items over their head.

Lateral Epincondyle

The lateral epicondyle of the humerus is a small, tuberculated eminence, curved a little forward, and giving attachment to the radial collateral ligament of the elbow-joint and to a tendon common to the origin of the supinator and some of the extensor muscles. Specifically, these extensor muscles include the anconeus muscle, the supinator, extensor carpi radialis brevis, extensor digitorum, extensor digiti, and extensor carpi ulnaris.

A common injury associated with the lateral epicondyle of the humerus is lateral epicondylitis also known as tennis elbow. Repetitive overuse of the forearm, as seen in tennis or other sports, can result in inflammation of "the tendons that join the forearm muscles on the outside of the elbow. The forearm muscles and tendons become damaged from overuse. This leads to pain and tenderness on the outside of the elbow.

Radius

The forearm contains two major bones. One is the ulna, and the other is the radius. In concert with each other, the two bones play a vital role in how the forearm rotates. The ulna primarily connects with the humerus at the elbow joint, while the radius primarily junctions with the carpal bones of the hand at the wrist joint. The two bones play only secondary roles at their opposing joints. The radius is the home for a few muscles' insertion points. The biceps originate near the shoulder joint and insert into the radial tuberosity on the upper part of the radius, near the elbow joint. Other muscle attachments include the supinator, the flexor digitorum superficialis, the flexor pollicis longus, the pronator quadratus, and many more tendons and ligaments. Due to the human instinct to break a fall by outstretching the arms, the radius is one of the more frequently fractured bones in the body. Also, dislocation issues with both the wrist and the elbow may arise.

Brachioradilus

The brachioradialis muscle is located in the forearm. It enables flexion of the elbow joint. The muscle also assists with pronation and supination of the forearm. These two movements allow the forearm and hand to turn so that the palm faces up or down. The arms are the only part of the body with this ability. The muscle originates on the lateral supracondylar ridge of the humerus. This rough margin is located on the lower end of the humerus. From there, the brachioradialis travels the length of the forearm. It inserts into the distal radius, at the bony projection known as the radial styloid process. For oxygenated blood, the brachioradialis muscle relies on the services of the radial recurrent artery. This artery branches off of the radial artery just below the elbow. The radial nerve innervates the muscle. The muscle shares this nerve with the triceps, anconeus, and extensis carpi radialis longus muscles.

Flexor Muscles

Flexor Carpi Radialis

The flexor carpi radialis muscle is a relatively thin muscle located on the anterior part of the forearm. It arises in the humerus epicondyle, close to the wrist area. It is a superficial muscle that becomes very visible as the wrist comes into flexion. The muscle travels on the outside of the flexor digitorum superficialis. It inserts at the base of the index finger. The innervation of this muscle is provided by the median nerve and it receives its blood supply through the radial artery. It performs the function of providing flexion of the wrist and assists in abduction of the hand and wrist. If this muscle becomes weak, it can be strengthened with the help of movements that provide resistance against its flexion. Dumbbells, wrist curls and wrist rollers can be used to exercise this muscle and add to its strength. The flexor carpi radialis muscle is located close to the palm side of the arm, which allows it to bend the wrist on its side. This helps to reduce the angle between the forearm and the thumb. The wrist remains straight and does not extend or bend backwards.

Flexor Carpi Ulnaris

The anterior muscles of the forearm consist of three layers, the superficial, intermediate, and deep flexors. All three layers are located in the flexor compartment.

Among the superficial muscles is the flexor carpi ulnaris. It arises, along with the other superficial muscles, from the medial epicondyle of the humerus. But the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle has an additional attachment point on the head of the ulna. It inserts at two wrist bones: the pisiform bone and the hook of the hamate. It also inserts at the base of the pinky finger.

Blood is supplied to the muscle by the ulnar collateral arteries and the anterior and posterior ulnar recurrent arteries. It also receives blood from small branches of the ulnar artery. The flexor carpi ulnaris is enervated by the ulnar nerve.

The flexor carpi ulnaris muscle works in tandem with the extensor carpi ulnaris. These muscles flex the wrist and adduct it (move it laterally in the direction of ulnar).

Flexor Digitorum Superficialis

The flexor digitorum superficialis is an extrinsic muscle that allows the four medial fingers of the hand to flex. These fingers include the index, middle, ring, and pinkie fingers. The term extrinsic means that the muscle is located in the forearm. This muscle has two distinct heads, which both originate in the forearm. The humeroulner head originates at the medial epicondyle of humerus, which refers to a knuckle-like projection on the part of the upper arm bone that is closest to the elbow. This head also originates from the ulnar collateral ligament and coronoid process of ulna, which refers to a triangular projection on the ulna. The ulna is one of the bones of the forearm. The other head, known as the radial head, originates from the back portion of the radius, a bone of the forearm. Four tendons arise from this muscle close to the wrist and pass via the carpal tunnel. The tendons split and insert on the sides of the middle phalanges of the four medial fingers. In many cases, the tendon is absent from the little finger. This is known as an anatomical variant. In turn, this may result in problems with the diagnosis of an injury of the little finger. Each of the four medial fingers contains three bones. These are the distal phalanges at the fingertips, the middle phalanges, and the proximal phalanges which are closest to the palm. The primary action of the flexor digitorum superficialis is to flex the fingers at the proximal interphalangeal joints. These hinge joints are located between the between the middle and proximal phalanges. The secondary role of the muscle is to flex the metacarpophalangeal joints. These are located between the proximal phalanges and the metacarpal bones of the palm.

The muscle receives oxygen-rich blood from the ulnar artery. It is innervated by the median nerve.

Pronator Teres

The pronator teres muscle is located on the palmar side of the forearm, below the elbow. Aided by the pronator quadratus, its function is to rotate the forearm palm-down. This is also known as pronation. The pronator teres muscle has two heads:the humeral head and the ulnar head. As the names imply, they connect the ends of the humerus and the ulna to the radius. The humeral head is the larger and shallower of the two. It begins above the medial epicondyle, on the medial supracondylar ridge and the common flexor tendon. The ulnar head originates below the elbow on the inside of the coronoid process of the ulna. The two heads come together, cross the forearm diagonally, and insert halfway down the lateral surface of the radius via a tendon. The pronator teres is innervated by the median nerve. Pronator teres syndrome is sometimes attributed to neurogenic pain in the wrist. It is caused by overactivity of the pronator teres muscle in which the median nerve becomes entrapped. Repetitive throwing or turning of a screwdriver can cause pronator teres syndrome.

Medial Epicondyle

![]()

The medial epicondyle of the humerus in humans is larger and more prominent than the lateral epicondyle and is directed slightly more posteriorly in the anatomical position.

It gives attachment to the ulnar collateral ligament of elbow joint, to the Pronator teres, and to a common tendon of origin (the common flexor tendon) of some of the Flexor muscles of the forearm.

The ulnar nerve runs in a groove on the back of this epicondyle. The medial epicondyle protects the ulnar nerve. The ulnar nerve is vulnerable because it passes close to the surface along the back of the bone. Striking the medial epicondyle causes a tingling sensation in the ulnar nerve. This response is known as striking the “funny bone”. The name funny bone could be from a play on the words humorous and humerus, the bone on which the medial epicondyle is located. The medial epicondyle is located on the distal end of the humerus. Additionally, the medial epicondyle is inferior to the medial supracondylar ridge. It is also proximal to the olecranon fossa.

Ulna

The ulna is one of two bones that give structure to the forearm. The ulna is located on the opposite side of the forearm from the thumb. It joins with the humerus on its larger end to make the elbow joint, and joins with the carpal bones of the hand at its smaller end. Together with the radius, the ulna enables the wrist joint to rotate. The ulna is 50 percent larger in diameter than the radius at 4 to 5 months of age. During adult life, when remodeling and resorption are complete, the ulnar diameter becomes half that of the radius. The ulna is found, and has similar function, in both humans and four-footed animals, such as dogs and cats. If the ulna breaks, it will most commonly occur at either the point where the radius and ulna form a joint or where the ulna forms a joint with the hand's carpal bones. Ulnar fractures cause severe pain, difficulty in moving the joint affected, and even deformity of the arm if the fracture is compound.

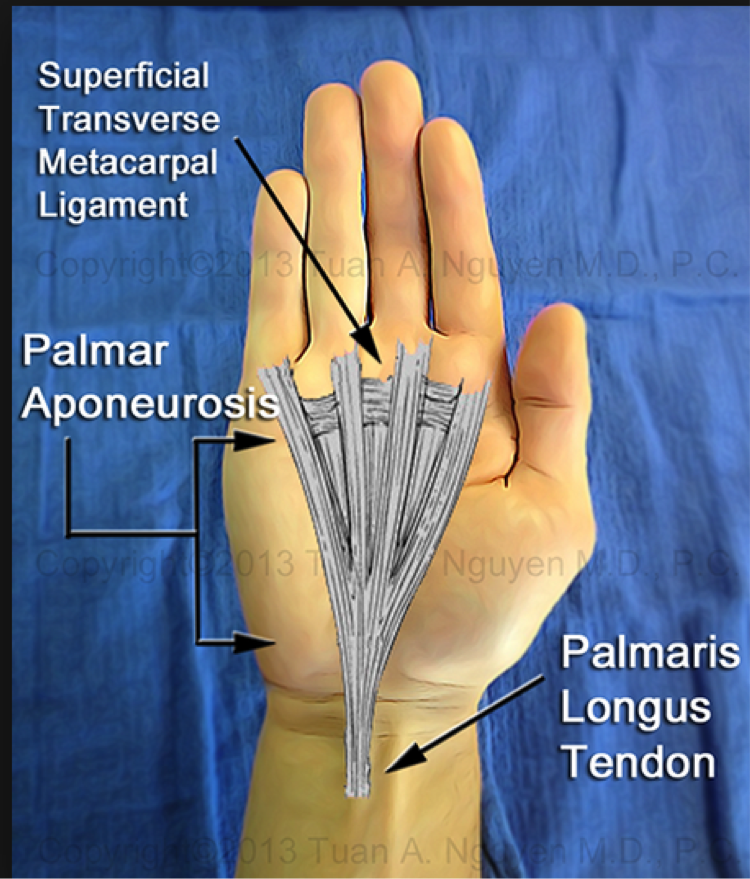

Palmar Aponeurosis

The palmar aponeurosis is a fibrotendinous complex that functions as the tendinous extension of the palmaris longus, when present, and as a strong stabilizing structure for the palmar skin of the hand. It has five longitudinal slips that project into the base of each digit and a deeper transverse portion that crosses the palm at the proximal end of the metacarpals bones.

Palmaris Longus

The palmaris longus muscle is one of five muscles that act at the wrist joint. The palmaris longus muscle is a long muscle that runs to the palm and activates flexibility at the wrist. Muscles assist in movement, blood flow, speech, heat production, body shaping, and protection of some internal organs. How muscles attach depends on function and location, and may attach directly to skin or bone. Tendons attach bone to muscle. Ligaments attach bone to bone. An aponeurosis is a strong, flat connective tissue that attaches to muscle. Fascia is tissue that connects muscle to muscle or muscle to skin. The two ends of a skeletal muscle's attachment are "insertion" and "origin." The insertion end is the part that attaches to the moveable bone that will move when contracted. The palmaris longus muscle starts up near the elbow and runs across the middle of the forearm, where it inserts on the palmar aponeurosis. The palmaris longus muscle is absent in approximately 14 percent of the population, but has no affect on tightening and clenching ability. When present, the palmaris longus muscle is visible at the palm side of the wrist when flexed.

Obliques

Internal Oblique

The internal oblique is an abdominal muscle located beneath the external abdominal oblique.

This muscle originates at the lumbar fascia (a connective tissue that covers the lower back), the outer portion of the inguinal ligament (a ligament located on the bottom-outer edge of the pelvis), and back of the iliac crest (the upper-outside portion of the pelvis). The internal abdominal oblique muscle ends at the bottom edge of the rib cage, the rectus sheath (fibrous tissue that covers the abdominal muscles), and the pubic crest (an area in the lower-front of the pelvis).

The internal abdominal oblique muscle is located closer to the skin than the transverse abdominal muscle.

This muscle supports the abdominal wall, assists in forced respiration, aids in raising pressure in the abdominal area, and rotates and turns the trunk with help from other muscles.

The internal abdominal oblique muscle is an opposing force to the diaphragm, reducing upper chest cavity volume during exhalation. As the diaphragm contracts, the chest cavity is pulled down to increase lung size.

The contraction of this muscle also rotates the trunk and bends it sideways by pulling the midline and rib cage toward the lower back and hip. Internal abdominal oblique muscles are called “same side rotators.” The right internal oblique works with the left external oblique, and vice versa, when flexing and rotating the torso.

External Oblique

The external oblique muscle is one of the largest parts of the trunk area. Each side of the body has an external oblique muscle.

The external oblique muscle is one of the outermost abdominal muscles, extending from the lower half of the ribs around and down to the pelvis. Its lowest part connects to the the top corner of the pelvis (called the crest of the ilium), the bottom-front of the pelvis (the pubis), and the linea alba, a band of fibers that runs vertically along the inside of the abdominal wall. Together, the external oblique muscles cover the sides of the abdominal area. The intercostal and subcostal nerves connect the external oblique muscles to the brain.

The external obliques on either side not only help rotate the trunk, but they perform a few other vital functions. These muscles help pull the chest, as a whole, downwards, which compresses the abdominal cavity. Although relatively minor in scope, the external oblique muscle also supports the rotation of the spine.

Since the muscle contributes to a variety of trunk movements, strain or injury to the muscle can be debilitating. This may include movements that do not directly use the muscle. For example, ambulatory motions such as walking or running, which cause slight movements in the torso.

Rectus Abdominus

The rectus abdominis muscle is located in the front of the body, beginning at the pubic bone and ending at the sternum. It is located inside the abdominal region.

The muscle is activated while doing crunches because it pulls the ribs and the pelvis in and curves the back. The muscles are also used when a child is delivered, during bowel movements, and coughing. Breathing in and holding the rectus abdominis in pulls in the abdomen.

When this muscle is exercised and layers of fat disappear from the abdomen, the exposed rectus abdominis muscle creates the look of a “six pack.” Strengthening the muscle also improves performance in sports that require jumping.

The three muscles of the lateral abdominal wall — the internal oblique, the external oblique, and the transverse abdominis — have fibrous connections that create the rectus sheath, which crosses over and under the rectus abdominis. When doctors perform ultrasound-guided techniques on patients (such as a liver biopsy), they sometimes start scanning at the rectus abdominis muscle to distinguish between the internal oblique, transverses abdominis, and the peritoneal cavity.

MUSCLES OF THE UPPER BODY

Trapezius

The trapezius is one of the major muscles of the back and is responsible for moving, rotating, and stabilizing the scapula (shoulder blade) and extending the head at the neck. It is a wide, flat, superficial muscle that covers most of the upper back and the posterior of the neck. Like most other muscles, there are two trapezius muscles – a left and a right trapezius – that are symmetrical and meet at the vertebral column.

The trapezius arises from ligaments at its origins along the nuchal crest of the occipital bone and the spinous processes of the cervical and thoracic vertebrae

It extends across the neck and back to insert via tendons on the clavicle, acromion, and spine of the scapula. The name trapezius is given to this muscle due to its roughly trapezoidal shape; the long base of the trapezoid is formed at the origins along the vertebrae and the short base forms at the insertions along the scapula and clavicle.

The trapezius can be divided into three bands of muscle fibres that have distinct structures and functions within the muscle.

- The superior fibres cover the posterior and lateral sides of the neck with their tendons connecting to origins along the occipital bone and insertions on the clavicle.

- Just below this region is the narrow band of the middle fibres, which extend from origins along the superior thoracic vertebrae and insert into the acromion process of the scapula.

- Finally, the inferior fibres cover a wide region of the back from their origins along the inferior thoracic vertebrae and insert into the spine of the scapula.

The functions of the trapezius are diverse and are best understood by actions of the individual bands of muscle fibres within the trapezius. The superior fibers typically act upon the scapula by elevating it (as in shrugging) or by bracing the shoulder when a weight is carried. When other muscles hold the scapula in place, the superior fibres of both trapezius muscles can extend the head at the neck by pulling the occipital bone closer to the scapula. The middle fibres work to retract and adduct the scapula by pulling the shoulder blade closer to the spine. The inferior fibres depress the scapula by pulling it closer to the inferior thoracic vertebrae. To rotate the scapula, the inferior and superior fibres work together to push the inferior angle of the scapula laterally and raise the acromion. Finally, the trapezius stabilizes the scapula to prevent extraneous movement by lightly contracting all of its fibre bands simultaneously.

Deltoid Muscle

The deltoid muscle is a rounded, triangular muscle located on the uppermost part of the arm and the top of the shoulder. It is named after the Greek letter delta, which is shaped like an equilateral triangle. The deltoid is attached by tendons to the skeleton at the clavicle (collarbone), scapula (shoulder blade), and humerus (upper arm bone). The deltoid is widest at the top of the shoulder and narrows to its apex as it travels down the arm. Contraction of the deltoid muscle results in a wide range of movement of the arm at the shoulder due to its location and the wide separation of its muscle fibres.

The deltoid has three origins: the lateral end of the clavicle, the acromion of the scapula at the top of the shoulder, and the spine of the scapula. Each origin gives rise to its own band of muscle fibers with the anterior band forming at the clavicle, the lateral fibers forming at the acromion, and the posterior fibres forming at the spine of the scapula. The bands merge together as they approach the insertion point on the deltoid tuberosity of the humerus.

The deltoid has three distinct functions that correspond to the three bands of muscle fibres. Contraction of the anterior fibres flexes and medially rotates the arm by pulling the humerus towards the clavicle. Flexion and medial rotation of the arm moves the arm anteriorly, as in reaching forward or throwing a ball underhand. The lateral fibres abduct the arm by pulling the humerus toward the acromion. Abduction of the arm results in the arm moving away from the body, as in reaching out to the side. Contraction of the posterior fibres extends and laterally rotates the arm by pulling the humerus toward the spine of the scapula. Extension and lateral rotation moves the arm posteriorly, as in reaching backwards or winding up to throw a ball underhand.

Infraspinitus

The infraspinatus muscle is one of the rotator cuff muscles. The stability of the shoulder joint is mainly provided by the tendons of the subscapularis, teres minor, infraspinatous, and supraspinatous muscles that together form the rotator cuff. The cuff is fused to the underlying joint capsule except inferiorly. Because of the lack of inferior stability, most dislocations or subluxations occur in this direction. The shoulder is most vulnerable when fully abducted and a force from a superior origin is applied.

Teres

The teres minor muscle rotates the arm laterally and assists in bringing it toward the body. As it draws the upper arm bone (humerus) up, it strengthens the shoulder joint. There are two teres muscles. The other one is the teres major muscle, a thick, flattened muscle that brings the arm toward the body and assists in extending it when the arm is in a flexed position. The teres major muscle also aids in rotating the arm but its function is just the opposite of the teres minor and other muscles in the rotator cuff.

The teres major muscle is a thick, flattened muscle that brings the arm toward the body and assists in extending it when the arm is in a flexed position. There are two teres muscles. The other one is the teres minor muscle, which rotates the arm laterally and assists in bringing it toward the body. As it draws the upper arm bone (humerus) up, it strengthens the shoulder joint. The teres major muscle also aids in rotating the arm but its function is just the opposite of the teres minor and other muscles in the rotator cuff.

Triceps

Triceps Brachii Lateral Head

The lateral head of the triceps brachii muscle is a muscle of the back of the arm, originating from the back of the humeral shaft and inserting at the elbow. The triceps brachii has three heads (connective immovable muscle) and is the only muscle on the back of the upper arm. It connects the humerus (upper arm bone) and the scapula (shoulder blade) to the ulna (longest of the forearm bones) and is the primary extensor of the elbow. The three heads are the lateral, the medial, and the long head.

Triceps Brachii Long Head

The long head of the triceps brachii muscle is a muscle of the back of the arm, originating from the scapula and shoulder to insert at the elbow. The triceps brachii has three heads (connective immovable muscle) and is the only muscle on the back of the upper arm. It connects the humerus (upper arm bone) and the scapula (shoulder blade) to the ulna (longest of the forearm bones) and is the primary extensor of the elbow. The three heads are the lateral, the medial, and the long head. The long head of the triceps brachii muscle, apart from the other triceps muscles, has a role in stabilizing the shoulder joint.

Latissimus Dorsi

The latissimus dorsi muscle, whose name means “broadest muscle of the back,” is one of the widest muscles in the human body. Also known as the “lat,” it is a very thin triangular muscle that is not used strenuously in common daily activities but is an important muscle in many exercises such as pull-ups, chin-ups, lat pulldowns, and swimming.

The latissimus dorsi muscle has its origins along the lumbodorsal fascia of the lower back, arising from the inferior thoracic and lumbar vertebrae, sacrum, iliac crest, and the four most inferior ribs From its many widespread origins, it runs obliquely, superiorly and laterally through the back and armpits to insert on the posterior side of the humerus of the upper arm. As the latissimus dorsi approaches its insertion point, the many muscular fibres from its many origins merge to a point, giving the muscle a triangular shape.

The latissimus dorsi has several different functions, all of which involve movements of the arm. The primary function of the lat is the adduction of the arm, which is often used when performing a pull-up or chin-up or when pulling a heavy object down from a shelf above one’s head. Another function of the lat is extension of the arm, as in swinging the arm toward the back. This motion is used when swinging the arms while walking as well as during rowing exercises. Finally, the latissimus dorsi medially rotates the arm, moving the front of the arm towards the body’s midline. When performed with a bent elbow, medial rotation of the arm brings the hand towards the chest, like when folding the arms or touching the elbow on the opposite arm.

Extensor Muscles Of The Forearm

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7F4dHDwwvhQ

The extensor carpi radialis longus muscle runs along the lateral side of the forearm, connecting the humerus (upper arm bone) to the hand. It functions to extend the wrist and assists in abducting the hand.

Gluteus Maximus

The gluteus maximus muscle is located in the buttocks and is regarded as one of the strongest muscles in the human body. It is connected to the coccyx, or tailbone, as well as other surrounding bones. The gluteus maximus muscle is responsible for movement of the hip and thigh.

Standing up from a sitting position, climbing stairs, and staying in an erect position are all aided by the gluteus maximus.

Pain while rising to a standing position or lowering to sit may be caused by gluteus maximus syndrome. This syndrome is caused by a spasm in the muscle of the gluteus maximus. The pain usually disappears when sitting and affects only one side of the body.

Other causes of pain can be caused by an inflammation of the tendons or friction between the bones, tendons, and gluteus maximus muscle; these conditions are referred to as either bursitis or tendinitis. Treatments for these disorders include physical therapy or anti-inflammatory pills or injections. Physical therapists may try to put pressure on the joint of the gluteus maximus muscle and coccyx, or recommend exercises to reduce pain and improve range of motion.

Biceps Femoris

The biceps femoris is a double-headed muscle located on the back of thigh. It consists of two parts: the long head, attached to the ischium (the lower and back part of the hip bone), and the short head, which is attached to the femur bone.

The long head is a part of the hamstring muscle group that occupies the posterior section of the thigh. The hamstring muscles may be considered extensors of the thigh. The biceps femoris muscle is important for knee flexion, internal and external rotation, and hip extension.

Pain in the biceps femoris can be caused by several reasons. The most common condition is a strained muscle caused by improper lifting or too much exercise. Overuse of the biceps femoris can result in torn muscles and ligaments.

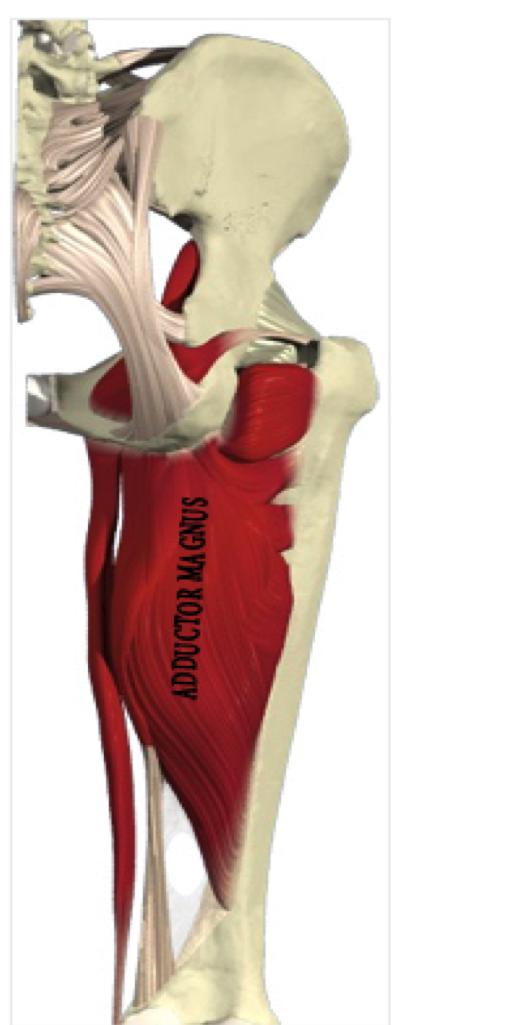

Adductor Magnus

On the medial side (closest to the middle) of the thigh, the adductor magnus muscle creates the shape of a large triangle. As an adductor, it contracts and pulls the hip towards the body's midline. This action is a fundamental part of walking, sprinting, and a variety of other bipedal motions. The muscle also extends the hip. While an adductor, the muscle is often considered to be part of the hamstring group as well.

The muscle originates in the pelvic region; specifically, it arises from the pubis and the tuberosity of the ischium, which are also known as the sitz or sitting bones. Then, the muscle inserts into several parts of the femur bone.

Oxygenated blood arrives at the adductor magnus muscle via the obturator artery, which branches from the internal iliac artery. Once blood is depleted of oxygen, the obturator veins drain into the venal system.

For adductive motion, innervations come by way of the inferior branch of the obturator nerve. For hamstring functions, the muscle is served by the sciatic nerve.

Semitendonosis

The semitendinosus muscle is one of three hamstring muscles that are located at the back of the thigh. The other two are the semimembranosus muscle and the biceps femoris. The semitendinosus muscle lies between the other two. These three muscles work collectively to flex the knee and extend the hip.

The semitendinosus muscle begins at the inner surface of the base of the pelvis (known as the tuberosity of the ischium) and the sacrotuberous ligament. It inserts at the medial tibial condyle.

The semitendinosus muscle is comprised primarily of fast twitch muscle fibres. Fast twitch muscle fibres undergo rapid contractions for a short time period and easily wear themselves out.

The inferior gluteal artery and the perforating arteries bring oxygenated blood to the semitendinosus muscle. A segment of the sciatic nerve serves as the sensory and motor nerve for the muscle.

When the semitendinosus muscle becomes overly strained, a pulled hamstring results. There are three grades of pulled hamstring that are defined by how excessive the muscle tear is and the degree of pain and disability.

Gastrocnemius

The gastrocnemius muscle is a muscle located on the back portion of the lower leg, being one of the two major muscles that make up the calf. The other major calf muscle, the soleus muscle, is a flat muscle that lies underneath the gastrocnemius. Both the gastrocnemius and the soleus run the entire length of the lower leg, connecting behind the knee and at the heel. A third muscle, the plantaris muscle, extends two-to-four inches down from the knee and lies between the gastrocnemius and the soleus.

The gastrocnemius branches at the top behind the knee; the two branches are known as the medial and lateral heads. The flexing of this muscle during walking and bending of the knee creates traction on the femur, pulling it toward the tibia in the lower leg and causing the knee to bend. Both the gastrocnemius muscle and the soleus join onto the Achilles tendon, which is the strongest and thickest tendon in the human body. The tendon originates about six inches above the heel, running down the center of the leg to connect to the heel below the ankle.

Soleus

The soleus is the plantar flexor muscle of the ankle. It is capable of exerting powerful forces onto the ankle joint. It is located on the back of the lower leg and originates at the posterior (rear) aspect of the fibular head and the medial border of the tibial shaft.

The soleus muscle forms the Achilles tendon when it inserts into the gastrocnemius aponeurosis. The tibial nerves S1 and S2 innervate it; arterial sources include the sural, peronial, and posterior tibial arteries.

The soleus muscle is primarily used for pushing off the ground while walking. It may be exercised through calf raises while standing up or sitting down. The soleus is vital to everyday activities such as dancing, running, and walking. The soleus muscle helps to maintain posture by preventing the body from falling forward.

The soleus is also part of the skeletal-muscle pump, which is a collection of muscles that help the heart circulate blood. Veins within the muscles become compressed and decompressed as the muscles surrounding them contract and relax. This aids in venous return of blood to the heart.

Lower Body Muscles

MUSCLES OF THE LOWER BODY

Iliopsoas

The iliopsoas muscle belongs to the inner hip muscles. It comprises a complex of two muscles with different areas of origin. This muscle belongs to the striated musculature and the innervation is carried by the femoral nerve as well as direct branches of the lumbar plexus. The iliopsoas muscle consists of:

- Psoas major muscle: originates from the 1st to 4th lumbar vertebrae, the costal processes of all lumbar vertebrae and the 12th thoracic vertebrae and inserts at the lesser trochanter of the femur.

- Iliacus muscle: runs from the iliac fossa to the lesser trochanter.

The Iliopsoas major and iliacus muscle unify in the lateral pelvis shortly before the inguinal ligament becoming the iliopsoas muscle. There they pass below the inguinal ligament through the muscular lacuna together with the femoral nerve. Both muscles are completely surrounded by the iliac fascia. The lumbar plexus lies dorsally from the psoas major muscle which is penetrated by the genito femoral nerve. Medially from the psoas major runs the sympathetic trunk. The iliopsoas muscle is the strongest flexor of the hip joint (important walking muscle). In the supine position it decisively supports the straightening of the upper body (e.g. during sit-ups). Furthermore it rotates the thigh laterally. A unilateral contraction leads to a lateral flexion of the lumbar vertebrae column. Altogether the iliopsoas muscle plays a significant role in the movement and stabilization of the pelvis.

Pectineus

The pectineus muscle is a small muscle located in the mid-thigh of the leg. Its physiological role is in the flexing and adducting (drawing inward toward the body) of the thigh. Due to its location and function, it is classified as a pelvic muscle. It is supplied with oxygen and nutrients by the femoral and deep femoral arteries of the leg and pelvis.

The pectineus muscle is located close to other muscles of the pelvis and thigh, such as the adductor longus, and forms part of the femoral triangle. It runs from the pelvis and along the femur in the upper leg. However, this muscle is relatively small in comparison to other muscles of the thigh. This muscle is unusual in that its exact anatomical location can differ slightly from person to person. It lies on the boundary of two compartments (functional groups) of muscles in the leg. The pectineus muscle can be placed in the anterior (front) or the medial compartment, and can also be innervated by two different nerves.

Quadriceps

The quadriceps femoris is a group of muscles located in the front of the thigh. The Latin translation of "quadriceps" is "four headed," as the group contains four separate muscles: the vastus lateralis, vastus medialis, vastus intermedius, and the rectus femoris. Each of the vastus muscles originates on the femur bone and attaches to the patella, or kneecap. The three vastus muscles are also partially covered by the rectus femoris, which also attaches to the kneecap. However, unlike the vastus muscles, the rectus femoris inserts into the hip bone.

The lateral femoral circumflex artery and its branches supply the quardriceps with oxygenated blood, and the femoral nerve (and its subsequent branches) innervates the muscle group. The quadriceps assist in extending the knee. Since these muscles are used often for walking, running and other physical activities, the quadriceps are prone to injuries including strains, tears and ruptures.

Sartorius

Long and thin, the sartorius muscle spans the distance of the thigh. It originates at anterior superior iliac spine (a bony projection on the uppermost part of the pelvis) and travels to the upper shaft of the tibia, or shinbone. As such, the sartorius is the longest muscle in the human body.

The muscle helps flex, adduct, and rotate the hip. In addition, it helps with the knee's flexion. The femoral artery supplies oxygen-rich blood to the muscle. It is innervated by the femoral nerve as well as the intermediate cutaneous nerve of the thigh.

The sartorius muscle may be susceptible to pes anserine bursitis, which also involves inflammation within the knee's medial (middle) portion. Typically, this condition results from overworking the muscle, and it is an occupational hazard for most athletes. Symptoms often include swelling, tenderness, and pain. Since the muscle covers a range of motion, severe injury such as a tear or rupture can be debilitating.

WASLA Teacher Librarian of the Year- 2017: Jo-Anne Urquhart

- 2016: Lise Legg

WASLA Library Officer of the Year- 2012: Karen Notley